Micromobility, mandatory insurance, and the case of pedelecs: between European law and the Portuguese transposition

The rapid surge in the use of electric vehicles — notably e-scooters, cargo bikes, and pedal-assist bicycles (pedelecs), among other forms of micromobility — has introduced new challenges in the realm of road safety.

In response to this evolving landscape, the European Union (EU) introduced regulatory measures aimed at safeguarding users through mandatory third-party liability insurance.

In 2021, the EU adopted Directive (EU) 2021/2118, which requires Member States to ensure that electric vehicles meeting specific criteria — namely, propulsion solely by mechanical means, speed, and weight thresholds — are covered by insurance. The Directive allows Member States some discretion in how they transpose these provisions into national law.

Portugal fulfilled this obligation in 2025 through Decree-Law No. 26/2025. However — whether by oversight or deliberate policy choice — the national legislation adopted a broader definition of “vehicle”, omitting the clause referring to “exclusively mechanically propelled” systems. This deviation has triggered a wave of legal uncertainty.

Ultimately, the inclusion or exclusion of certain vehicle types under the mandatory insurance framework hinges on how this definition is interpreted in practice.

According to Article 288 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), European Union law may take various forms, with regulations and directives being the most prominent.

- Regulation: a legislative act of general application, binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member States, without the need for national transposition.

- Directive: binding upon Member States as to the result to be achieved but leaving to national authorities the choice of form and means. Directives require transposition into domestic law within a defined timeframe and allow adaptation to national contexts.

Despite this formal flexibility, the case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) has been consistent in asserting that Member States must not compromise the essential objectives of a directive.

In Marleasing (Case C-106/89), the Court affirmed that national legislation must be interpreted, as far as possible, in the light of the wording and purpose of the relevant directive — even if the national text differs. This principle enables Portugal to broaden the definition of “vehicle” so long as it remains aligned with the directive’s objectives.

In Grimaldi (Case C-322/88), the Court clarified that while Member States may not narrow the scope of a directive, they are permitted to expand it to enhance protection — a legal foundation that supports the omission of the term “exclusively” in the Portuguese decree.

Directive 2021/2118 amends Directive 2009/103/EC and seeks to strengthen the protection of road traffic victims by ensuring that motor vehicles — including non-conventional ones — are covered by third-party liability insurance. It sets out a series of criteria to determine which vehicles fall under its scope.

“Vehicle means (a) any motor vehicle propelled exclusively by mechanical power with a design speed exceeding 25 km/h or a weight exceeding 25 kg and a speed exceeding 14 km/h, or (b) any trailer to be used with a vehicle referred to in point (a), whether coupled or uncoupled”

In other words, three cumulative conditions determine the scope of application:

- The vehicle must be propelled exclusively by mechanical power (i.e., without direct human input);

- It must have a design speed exceeding 25 km/h; or

- It must weigh more than 25 kg and be capable of reaching speeds over 14 km/h.

Portugal transposed this directive through Decree-Law No. 26/2025, published in 2025, but with one notable divergence: it adopted a broader definition of “vehicle”, omitting the word “exclusively”.

“A motor vehicle designed to travel on land, powered by mechanical force, with a maximum design speed exceeding 25 km/h, or a net weight over 25 kg and a speed above 14 km/h.”

By omitting the term “exclusively”, the legal framework potentially extends to hybrid-propulsion vehicles, such as pedelecs — even when mechanical propulsion is only activated through initial human effort.

Under the gold-plating principle, Member States are permitted to go beyond the minimum standards set out in a directive, provided they do not undermine its core objectives or create distortions within the internal market — which is arguably the case here.

The text of the Directive explicitly includes the following provisions:

“Since the entry into force of Directive 2009/103/EC, many new types of motor-powered vehicles have come onto the market. Some of them are powered by a purely electrical motor, some of them by auxiliary equipment. Such vehicles should be taken into account in defining the meaning of ‘vehicle’. That definition should be based on the general characteristics of such vehicles, in particular their maximum design speeds and net weights, and should provide that only vehicles propelled exclusively by mechanical power are covered. The definition should apply independently of the number of wheels that the vehicle has. Wheelchairs intended for use by persons with physical disabilities should not be included in the definition.”

“Light electric vehicles that do not fall within the definition of ‘vehicle’ should be excluded from the scope of Directive 2009/103/EC.”

“However, nothing in that Directive should hinder Member States from requiring, under their national law, motor insurance […] for any motor equipment used on land that does not fall within that Directive’s definition of ‘vehicle’.”

“Nor should that Directive hinder Member States from providing, in their national laws, for the victims of accidents caused by any other motor equipment to have access to the Member State’s compensation body.”

“Some motor vehicles are smaller and are therefore less likely to cause significant personal injury or damage to property than others. It would be disproportionate and not future proof to include them in the scope of Directive 2009/103/EC. Including them would also undermine the uptake of newer vehicles, such as electric bicycles that are not exclusively propelled by mechanical power, and discourage innovation. Furthermore, there is insufficient evidence that such smaller vehicles could cause accidents resulting in injured parties at the same scale as other vehicles, such as cars or trucks. In line with the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality, requirements at Union level should, therefore, cover only those vehicles that are defined as such in Directive 2009/103/EC.”

This excerpt highlights two key points:

- The Directive establishes a common European minimum, but Member States are free to go further in extending legal protection and mandating insurance for other categories of light electric vehicles.

- The Directive does not preclude Member States from regulating or compensating for accidents involving other types of motorised equipment, even if these fall outside the EU’s formal definition of a “vehicle”.

- Only vehicles propelled exclusively by mechanical power are covered, with electrically assisted bicycles — such as pedelecs — deliberately excluded from the scope.

This deliberate exclusion has also been reaffirmed in official statements by the European Parliament, which may be consulted in full at the following links:

- Press release Deal reached on new rules to better protect road accident victims: “electric bicycles […] are not required to have motor vehicle insurance.”;

- Press release Parliament adopts new rules to improve protection of road accident victims: “the revised rules exclude electric bicycles from the motor insurance requirement.”.

It is therefore essential to clarify what is meant by mechanical power — and, more specifically, to distinguish the types of propulsion that underpin the legal classification of vehicles.

Motive Power

This is a broad and generic term that refers to any form of energy or physical agent capable of producing movement. Its source may be:

- Natural (e.g., wind, gravity, water current);

- Human (muscular force);

- Mechanical (electric or combustion engine);

- Thermal, hydraulic, or electric.

Classical definition (Oxford Dictionary of Physics): “A motive force is any energy source capable of driving a mechanical system, regardless of its physical nature.”

Mechanical Force

This is a specific subset of motive power — namely, the form that manifests as mechanical work, i.e. the transmission of energy through physical systems (motors, gears, shafts, etc.) that cause a body to move.

- It always involves physical interaction between components (e.g., torque, traction, pushing force, rotation);

- It is typically associated with motors and engineered systems.

Mechanical force is thus defined as the result of a physical interaction that causes motion or deformation of a body, under the action of an external agent, and transmitted through a mechanical system. In the context of vehicles, it refers to force generated by a motorised mechanism that performs work on the propulsion system, enabling the vehicle to move independently of direct human muscular effort.

According to EN 15194:2017 — the European standard for Electrically Power Assisted Cycles (EPAC):

“Motor mechanical power means the power provided by a motor that exerts mechanical force to drive the vehicle.”

In the European legal and regulatory domain, particularly in instruments such as Regulation (EU) No 168/2013 on the approval of two- or three-wheel vehicles and quadricycles, the following definitions apply:

“Propulsion system: any mechanical configuration intended to impart motion to a vehicle by means of a motor using electrical, thermal, hydraulic, or hybrid energy conversion.”

“Mechanical power is the effective force produced by a motor system to impart movement to a vehicle through direct or indirect mechanical interaction.”

This definition serves as the benchmark criterion to determine whether a given vehicle falls within the scope of mandatory insurance and regulatory obligations currently in force.

The Specific Case of Pedelecs

Pedelecs (Pedal Electric Cycles) are bicycles equipped with electric pedal assistance. They are designed to retain the core functionality of a conventional bicycle, while providing motorised support to the rider.

How do they work?

- The user must initiate movement manually, by pedalling;

- A sensor detects the rider’s input and activates the electric motor, which provides assistance to the pedalling motion;

- The motorised assistance automatically disengages when:

-

- The rider stops pedalling;

- The bicycle reaches 25 km/h (the legal limit under EU law);

- Or the brakes are applied.

Key point: the motor cannot start the bicycle independently. Human muscular effort is essential for propulsion to begin.

Modified Pedelecs vs Conventional Pedelecs

The situation becomes more complex when examining modified pedelecs — that is, bicycles in which the motor has been altered to allow acceleration without pedalling, typically via throttles or manual controls. These versions are, in most Member States, illegal, and no longer meet the technical definition of a standard pedelec. They become, either wholly or partially, motorised vehicles, which has clear legal implications for their classification, insurance requirements, and regulatory treatment.

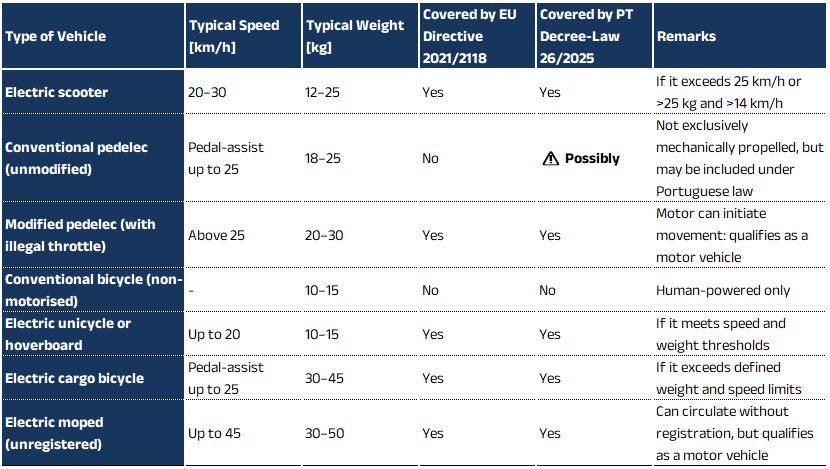

Table 1 – Comparison among micromobility vehicles

This study demonstrates that, although Directive (EU) 2021/2118 defines the concept of a vehicle as one propelled exclusively by mechanical power, Portugal adopted a broader definition in Decree-Law No. 26/2025, deliberately omitting the term “exclusively”. This legislative choice is supported by Article 288 of the TFEU and the case law of the CJEU, which allow Member States to adapt the transposition of directives, provided they respect the directive’s objectives — and may even extend the scope of application to offer greater protection.

Nonetheless, even seemingly minor variations in legal drafting can have significant practical consequences.

This study therefore examines the concept of motive and mechanical force, as well as the operational dynamics of pedelecs. Based on this analysis, it may be argued that pedelecs fall outside the scope of the decree since they are powered by human force and assisted by mechanical force — yet, in practice, this will ultimately depend on how enforcement authorities interpret and apply the legal provisions.

Latest news

All news

Collaborative mobility planning takes a major step forward in Alto Minho

This week, Ponte de Lima hosted an important milestone for sustainable mobility in the Alto Minho region, with the working sessions of the 2nd-generation Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan of Alto Minho (SUMP Alto Minho), promoted by CIM Alto Minho. At VTM, we are proud to support CIM Alto Minho in the development of a new-generation […]

VTM welcomes Oriol Riba and Alessandra Bernardi

VTM is pleased to announce the addition of two highly experienced professionals, Oriol Riba and Alessandra Bernardi, further strengthening our capabilities across infrastructure advisory and transport modelling. Oriol Riba joins VTM as a Senior Associate Director with more than fourteen years of experience in the infrastructure sector, with a strong focus on transport and additional exposure to energy […]